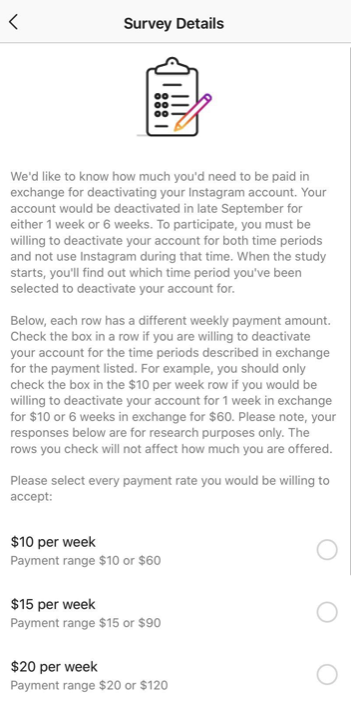

Intriguing screenshots, posted online by a Washington Post reporter this week, revealed an in-app pop-up from Instagram asking users to choose how much they’d be willing to receive to deactivate their account ahead of the US Election. Sums suggested for consideration ranged from $10-$20 a week.

Facebook, owner of Instagram, has had a controversial history around elections since the 2016 US Election which is now seen as a turning point for Big Tech’s impact on democracy. Facebook’s much-discussed role in the elections has been at the centre of post election tech ethics analysis globally.

So why are they asking users to log off in the 2020 election?

Facebook say they are now researching their impact on democracy, stung no doubt by the criticism of any part they may have played in the past. The company expects 200-400,000 users to opt in to the research project which will allow them to see how users interact with its products during the election period. They announce that “to continue to amplify all that is good for democracy on social media, and mitigate against that which is not, we need more objective, dispassionate, empirically grounded research“.

What has Facebook’s historical impact been on elections?

Even before the controversial 2016 election, there have been plenty of studies and research on the potential impact of Facebook on elections and on tech ethics. In 2012, a combined University of California, San Diego and Facebook research team argued that Facebook’s “I Voted” drove a small but measurable increase in turnout amongst young people. In 2014 a Harvard Law scholar wrote: “Facebook could decide an election without anyone ever finding out” and in April 2016 Rob Meyer published “How Facebook could tilt the 2016 election”.

All of these academics turned out to be on to something. Facebook did indeed have a significant impact on voter turnout and voting patterns in 2016. It was used by thousands of minor news sites to increase their engagement, unfortunately most often through spreading disinformation. In late October 2016 Buzzfeed contributors traced 100 pro-Trump sites to a Macedonian town of 45,000. Teens in the area had realised they could make money off the US election by setting up fake sites. They were a drop in the ocean however compared to the impact of alleged Russian interference. One study showed 340 million post shares alone associated with only 6 of the 470 Facebook pages that have been linked to Russian operatives.

So what part will Facebook play in 2020?

As November looms, Facebook will inevitably play a major role in the US election. Indeed, they have spent much of the last four years apologising for the impact that they had on the 2016 vote.

But only in January this year, an unapologetic Zuckerberg said that Facebook would not be changing the rules for political advertising. Revealing that politicians would still be exempt from the fact-checking program, permitted to spend millions on ads to target tiny portions of the electorate, and to use all the other tools Facebook currently offers to commercial clients. Alex Stamos, Facebook’s former chief security officer said that he believes that this was due in part to fear of political pushback.

However, by today (early September) Facebook has now revised its stance. The platform now says they won’t accept any new political ads in order to ensure a fair election. They’ve also tightened some of misinformation policies, such as deleting posts which claim voters will get Covid-19 if they vote in person. A change in policy designed, according to Zuckerberg, to limit the spread of misinformation in the last few days before the selection, which cannot be refuted in time.

What does this mean for tech ethics?

Though there has been little significant change in the policies Facebook employs regarding political campaigns between 2016 and 2020, public discourse has changed hugely. Until as late as August 2016, The Washington Post claimed Trump had run a very ‘analogue campaign’ in comparison to Clinton. Due to the highly targeted nature of the Trump campaign Facebook ads, liberal media journalists simply didn’t see them, and were unaware of their existence. Today, after the smallest details of the 2016 campaign have been poured over exhaustively, we know much more about their existence and the impact that they had.

Facebook doesn’t expect to release the findings of the current research until mid-year 2021, so we will know the result of the US Election itself well before we know about the impact Facebook may once again have had. But as the campaign draws to its conclusion, we can be sure once more that the tech giant’s platform is going to be the focus of campaign spending on both sides – and, subject to increasingly tech ethics-focused press attention.